The wind came like a freight train that night, gaining speed as it pummeled into the shores of Lake Michigan. Dark and angry waves crashed in an unending drum of rage as the rain fell in sheets and then buckets. As the wind continued to howl its lonesome blustery tune and the temperature continued to drop, ice began to accumulate on every exposed surface.

Ash trees, long rendered lifeless by the insatiable emerald ash borer, lined the shores and began to grow weary in the effort to support their icy limbs. Their rotted roots were no match for the roaring gusts and it’s only a matter of time…

Michigan ice storm in April 2018

Suddenly, a strong gust sends a towering ash to its horizontal grave. On its way down, it crashes into a helpless power line, the rural wire no match for the weight of the ice-laden tree. Instantly, hundreds of warm, illuminated homes are plunged into darkness: yard lights go out, furnace fans stop blowing, and panic rises up in their inhabitants as the storm rages on. How long will the power be out this time? And where did I put those damn candles?

Ivan kept warm by the propane heater while the battery slowly died on the iPad.

Luckily the pizza store had a generator.

Why won’t this flashlight turn on Daddy? Because you left it on for days son.

Can you get the power back Mr. Lineman? I left the flashlight on.

Ashley taped flashlights to the light fixture as night approached.

Scrabble battle illuminated by Ashley’s genius flashlight fixture.

Into this cold, dark fracas steps the lowly lineman, having been summoned from his warm slumber to restore power and safety to the neighborhood. He is a mechanic, electrician, woodsman, acrobat, carpenter, gadgeteer, and first-aider all rolled into one. But tonight, he is simply the lineman and he knows that when the weather gets nasty, he goes to work.

Within an hour, the lineman has found the break, cleared the dead ash tree, and climbed atop the icy pole to repair the line. The climbing spurs on his boots are perfectly filed and they bite deeply into the wooden pole as he steadily hauls his trusty toolbelt some 40 feet up. On his waistline workshop, he has his lineman’s pliers, skinning knife, wrenches, parts bag, screwdriver, folding rule, connectors, and a bag containing his all-important rubber gloves. He wraps his safety belt around the top of the pole, the length of it swaying in the inky night, and gets to work.

Just as the residents finally find the candles and matches, their lights flicker to life as they let out a collective sigh of relief. The lineman has restored power, but he will work long into the night to fully repair the damaged line. His hours are long and his work can be thankless, but he didn’t get into this line of work for glory; he just likes fixing things and helping folks out. Thank God for the lineman.

Telephone lineman Bob Lawrence circa 1950

The lineman’s occupation began in the 1840s with the widespread use of the telegraph. Telegraph lines needed to be strung coast to coast and the linemen would plant poles and string the lines that connected communities like never before. Thirty years later in the 1870s, these same lines were replaced with telephone lines as our communication took another innovative leap. When the push for residential electrification began in the 1890s, the linemen were again called up and their profession took a dangerous turn.

As a result of the inherent but relatively unknown dangers of working with electricity, nearly one in three linemen died from electrocution during the forty year period 1890-1930. ONE IN THREE. Needless to say, it was considered the most dangerous profession in existence at the time. Safety equipment and better practices followed, as did unions to fight for the workers’ rights and working conditions. The most prominent, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, still exists today.

Linemen amidst the chaotic lines

When FDR’s New Deal pushed for access to electricity for rural folks in the 1930s, there was a huge expansion of the lineman’s profession. “Boomers” was the colloquial name for the roving workers that traversed our great country to bring electricity to the farthest outposts of rural America. They were known to be rowdy risk-takers but they got the job done and many of their poles are still in use today.

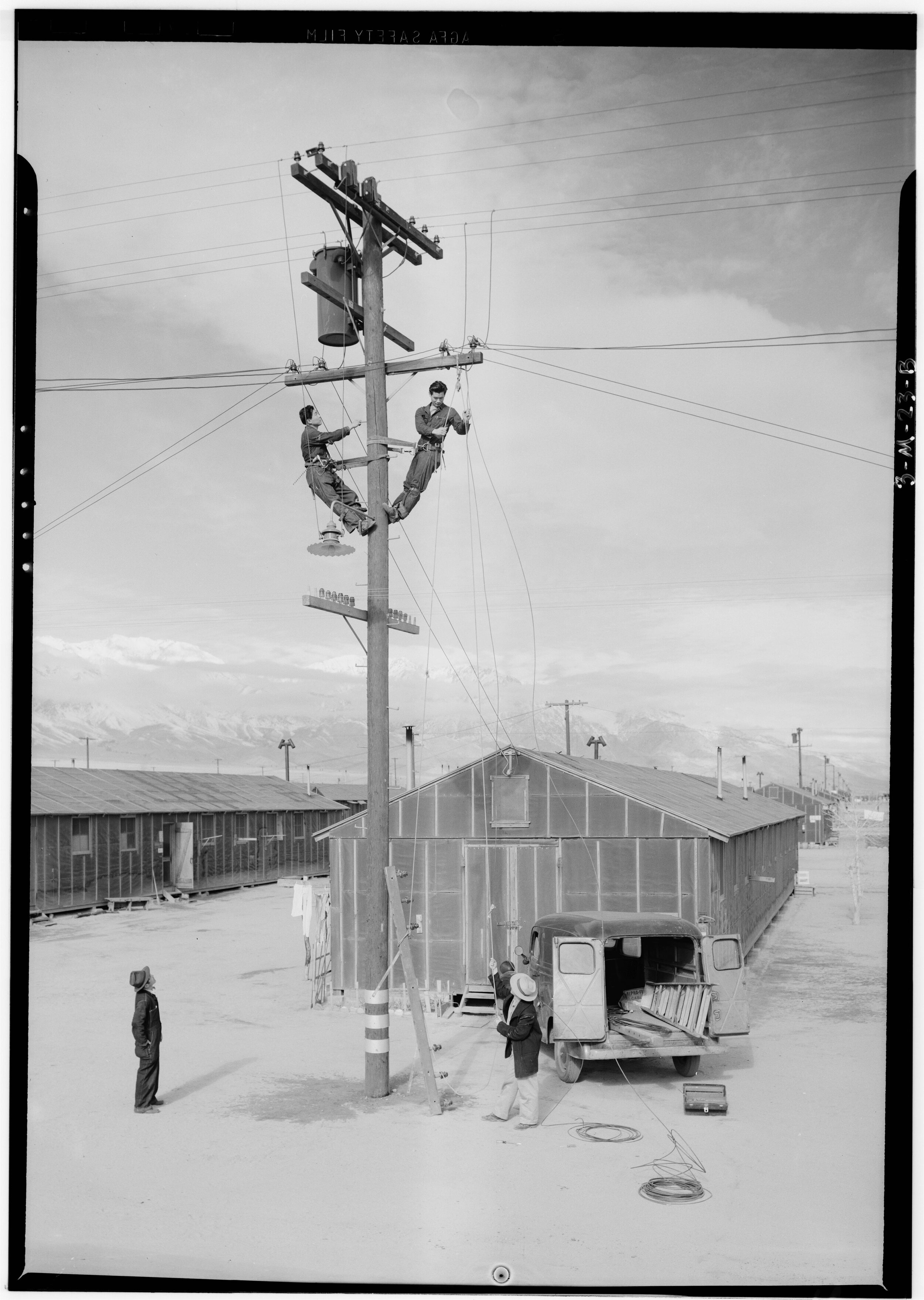

An Ansel Adams photograph of linemen in Manzanar, California

The profession changed a great deal during the 1940s and 1950s as the maintenance of existing lines became the main focus. This allowed the “boomers” to settle down in one place and be on-call, ready to repair damaged lines often taken out by storms and other natural disasters. Being a lineman was still incredibly dangerous as they were often atop forty-foot poles in terrible conditions trying to repair high-voltage wires, but at least they could enjoy the comforts of home when they were done.

Also during the 1950s, one of the lineman’s most useful innovations was invented: the cherry picker. In 1951, Walter E. Thornton-Trump invented The Giraffe, a hydraulic boom lift that has become a staple of a modern lineman’s arsenal and is now collectively known as a cherry picker. This machine allows linemen to quickly and safely access overhead lines, rendering the classic pole-climbing prowess of the lineman obsolete.

Linemen repairing a line in Seattle, circa 1952

To me, the lineman embodies a classic example of an underappreciated worker. Most of us take it for granted that our homes are powered each and every day with a steady stream of silent electricity, failing to realize the tireless work and hours of dedication (not to mention countless lives) that went into making that possible.

When our lights flicker off in a power outage, it’s easy to think of our own minute discomforts as we struggle in the dark to find the batteries for the flashlight, cursing our children for leaving them on in the drawer (does this happen to anyone else?). Next time, stop for a minute and think of the dedication of the men and women who go into those storms to repair the broken lines and bring light back into our homes. They are heroes worth celebrating and workers worth honoring.

The Lineman was a commissioned painting and has a home in Kansas, but prints are available HERE. Here’s to The Lineman!